Does water damage hair? The myth of “hygral fatigue”

How to cite: Wong M. Does water damage hair? The myth of “hygral fatigue”. Lab Muffin Beauty Science. January 28, 2026. Accessed January 28, 2026.

The way water interacts with hair is one of the biggest sources of myths about hair. One of the biggest myths is the idea that repeatedly wetting and drying the hair damages the hair naturally – commonly called “hygral fatigue”. This is not true!

Let’s dive into this…

This article is adapted from my video about hair extensions. Also check out Part 1 on hair and water for more!

Hair ties

A quick refresher on hair bonds (check out Part 1 for the full version):

- Water is very good at breaking the temporary bonds between hair proteins (especially hydrogen bonds)

- This is why wet hair breaks easily – there is less “glue” holding the hair proteins together, so less force is needed to separate them.

- Water also causes the cuticle scales to stick, as the surface of the cuticle scale absorbs less water than the bottom.

- When the hair is dry, these effects reverse

“Hygral Fatigue”

Because of these effects of water, it may seem that repeatedly wetting and drying the hair can damage the hair.

This persistent myth is called “hygral fatigue”, and is even mentioned in some peer-reviewed papers. It is often given as an excuse not to wash your hair every day. But there really isn’t much convincing evidence that this actually happens!

At the molecular level

An analogy I’ve seen is that this is like stretching a rubber band over and over again – with enough wetting and drying, the hair eventually gets “tired” and breaks.

But hair bands and rubber bands are very different. In rubber bands, stretching breaks permanent bonds that cannot be re-formed, and this eventually creates a crack.

In hair, water skips short-term hydrogen bonds that easily change – they form when you finish drying your hair. A better analogy would be assembling and assembling Lego pieces (not knockoffs, brand names), except the hydrogen-bonded atoms last much longer than this, since electrons and protons don’t wear out!

Related posts: Hair, hydration and water

However, hair is still very fragile when it’s wet, so frequent washing means more damage to hair if you don’t treat it well. But the water going in and out of the hair does not cause damage.

Hair drying tutorial

There are a few peer-reviewed papers that seem to support the idea that wetting and drying can naturally damage hair, but the evidence they present is not very convincing.

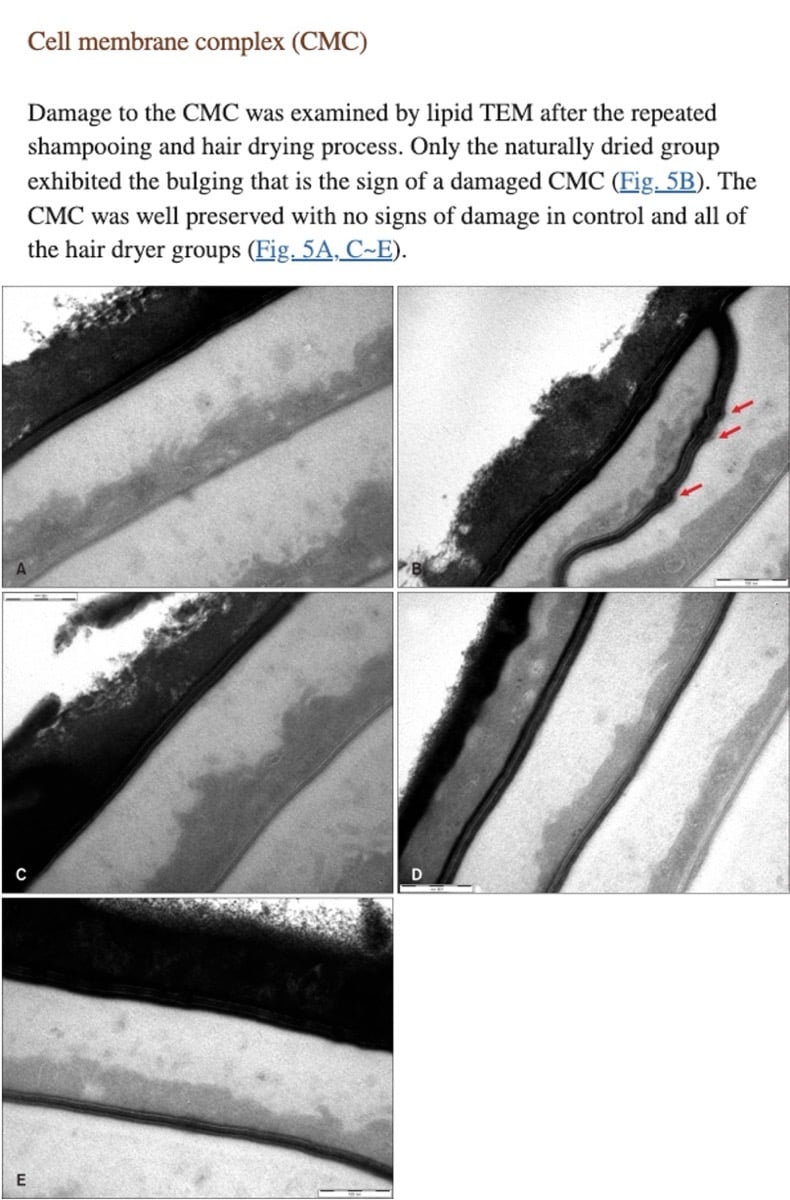

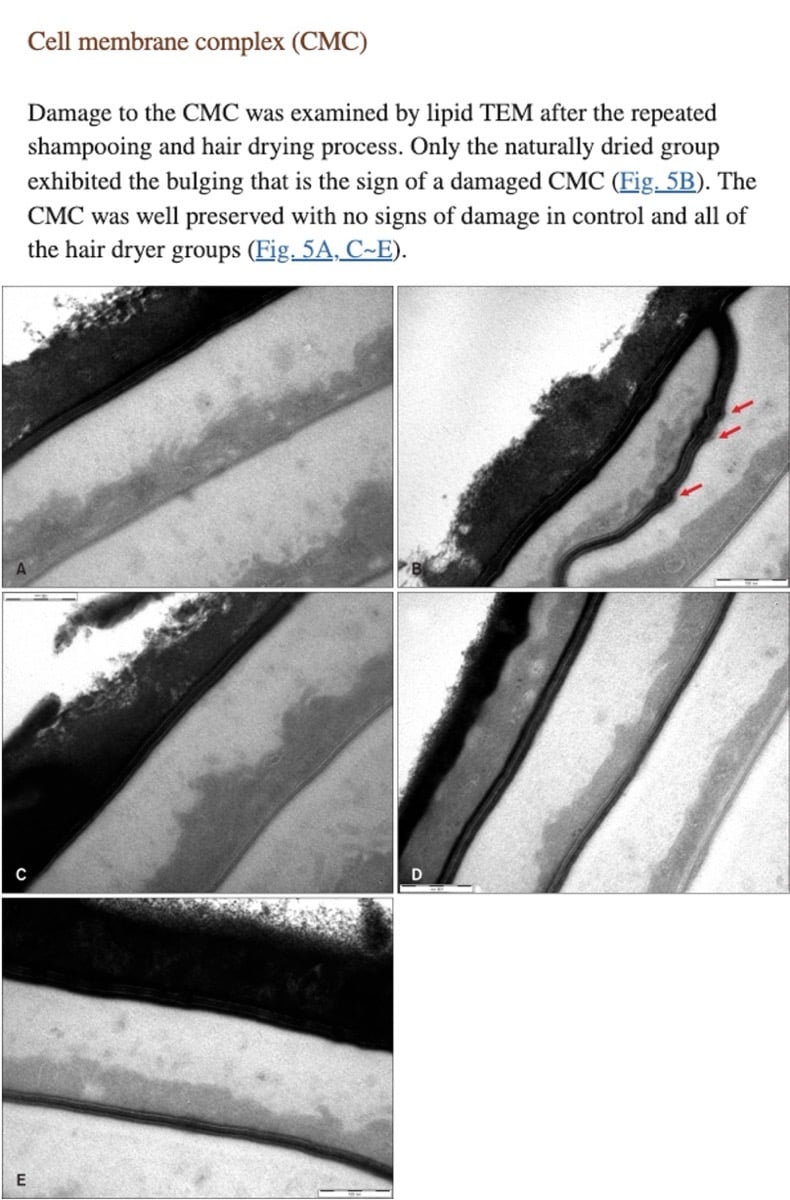

The first is a 2011 study on hair drying techniques (discussed in this article). The researchers looked at the damage from air drying versus using a hair dryer at different temperatures, resulting in different drying temperatures.

The researchers found that low temperature blow drying caused less damage. They saw bumps on a sample of air-dried hair, and concluded that this was water damage caused by prolonged swelling of the hair:

I don’t think their explanation makes sense. Air drying is common everywhere, including hair testing. If air drying was causing the bumps they saw, then other hair studies would be reporting this more.

Related post: How to dry your hair, according to science

It is very likely that the lumps are caused by something specific in this test. It is not clear how many times the researchers repeated these tests and measurements, so it is difficult to determine whether it is a problem with the experiment, or a fluke problem. But another possible explanation could be something that happened to that hair sample before it was collected for use, such as too much sun exposure.

Studies on coconut oil

A few studies have suggested that coconut oil can prevent the hair from absorbing water, and therefore protect itself from hygral fatigue.

A few of these studies explicitly use the term “hygral fatigue”. But they don’t actually mention any sources of hygral fatigue that occur in the first place.

It is also doubtful that coconut oil actually prevents the hair from absorbing water to any significant degree.

In some experiments, hair was coated with different oils (coconut, mineral and sunflower oil), and placed in a dynamic vapor sorption (DVS) machine. The weight of the hair was measured by the different moisture content – any added weight would be the water entering the hair. The water absorbed is then converted into a percentage of the hair’s weight. Since hair with coconut oil increased by a small percentage in weight, they concluded that coconut oil prevented the hair from absorbing too much water.

But Trefor Evans, another hair scientist, points out that this could be a trial error. Hair weighs more after adding coconut oil, so the same amount of water absorbed will look smaller as a percentage (actually you divide by a bigger number: hair + oil, rather than just hair).

A similar effect may be possible with studies measuring oiled hair after wetting it, then drying it again.

Coconut oil’s inability to hold more water makes sense when considering hair texture. All the edges of the cuticle is a gap – it is almost impossible to close most of the hair “pinecone” against small molecules of water. This concept boils down to the possibility that any hair treatment prevents water from entering or leaving the hair. The water content of your hair is highly dependent on relative humidity.

This does not mean that coconut oil does not benefit the hair. Oils act as lubricants on the surface of the hair, smoothing and protecting the cuticle from damage, such as when combing. Some studies suggest that coconut oil penetrates deeper into the hair than other oils. This means that coconut oil may fill the gaps in the fatty parts of the hair (the cell membrane complex “mud” between the hair cell “bricks”), which can help reduce the internal breakage of the hair.

Related post: Busting Hair Conditioner Myths: Build-Up, Silicones, Weighing Hair Down etc.

References

Robbins CR. Chemical and Physical Behavior of Human Hair. 5th ed. Springer Berlin Heidelberg 2012.

Lee Y, Kim YD, Hyun HJ, Pi LQ, Jin X, Lee WS. Damage to the hair shaft due to the heat and drying time of the hair dryer. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(4):455. doi:10.5021/ad.2011.23.4.455

Evans T. Estimating the water content of hair. Cosmetics & Toiletries. 2014;129(2):64-69.

Keis K, Huemmer CL, Kamath YK. Effect of oil films on vapor absorption of human hair. J Cosmet Sci. 2007;58(2):135-145.

Ruetsch SB, Kamath YK, Rele AS, Mohile RB. Secondary ion mass spectrometric investigation of the penetration of coconut and mineral oil into human hair fibers: Relevance to hair damage. J Cosmet Sci. 2001;52:169-184.

Rele AS, Mohile RB. The effect of coconut oil in preventing hair damage. Part I. J Cosmet Sci. 1999;50(6):327-339.

Rele AS, Mohile RB. The effect of mineral oil, sunflower oil, and coconut oil in preventing hair damage. J Cosmet Sci. 2003;54(2):175-192.

Kaushik V, Chogale R, Mhaskar S. Single hair fiber testing techniques to discriminate between mineral oil and coconut oil effect on physical properties of hair. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(4):1306-1317. doi:10.1111/jocd.13724

Gode V, Bhalla N, Shirhatti V, Mhaskar S, Kamath Y. Quantitative measurement of coconut oil penetration into human hair using radiolabeled coconut oil. J Cosmet Sci. 2012;63(1):27-31.